What first drew me back to the Church was its beauty. But when I started digging into its history, I found that beneath the public face of tradition and ritual, there is a record of events so bizarre and so thoroughly documented that they challenge everything we think we know about miracles and reality itself.

These aren’t Hallmark miracles for calendars and inspirational quotes. They are unsettling stories that disrupted empires and terrified entire cities. They involve kings, monks, saints, and ordinary people who were never the same afterward. They leave physical evidence, sworn testimony, liturgies, and feast days in their wake.

Set them beside modern encounter reports and they look like contact. Set them beside Scripture and they resemble warnings of floods and the predetermined downfall of kings. Maybe they are both. The best word for them is divine intervention. These stories have been buried but they should never have been forgotten.

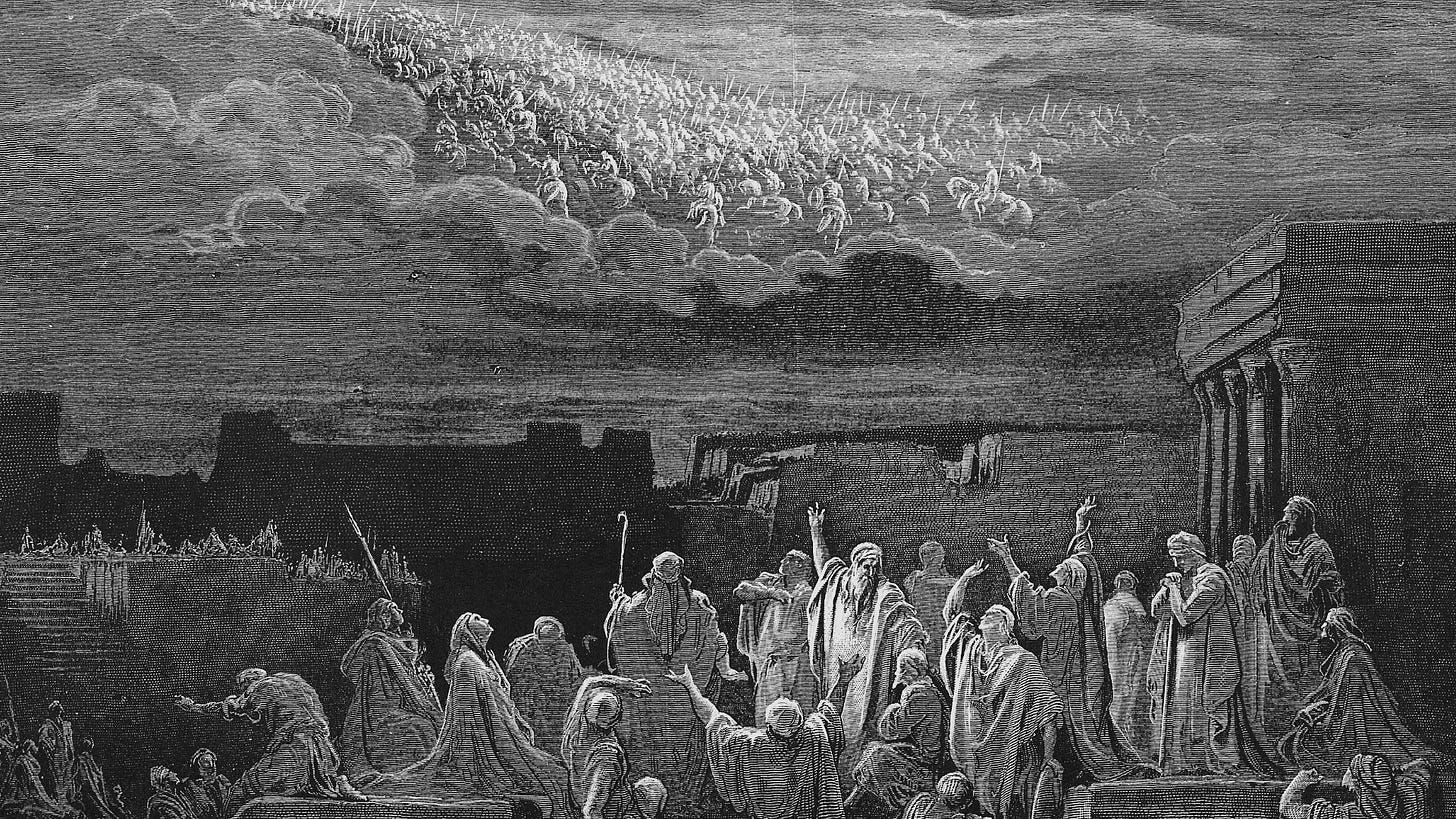

The earliest account I found comes from Jerusalem in the 1st century, during the First Jewish–Roman War. In 70 AD, as the Roman army surrounded the city in preparation to destroy the Temple, witnesses said the sky suddenly filled with lights.

The historian Flavius Josephus recorded it in his book, The Jewish War, where he wrote:

“Chariots and troops of soldiers in their armor were seen running about among the clouds, and surrounding of cities.”

Early Christian writers would later see this as a fulfillment of Christ’s warning that Jerusalem would be “surrounded by armies.” But even without that interpretation, the event stands on its own as a recorded phenomenon and a historical fact.

It is important to remember that Josephus, as a Jew, had no incentive to support Christian prophecy, yet he documented celestial armies moving in the sky.

A few centuries later, another phenomenon was reported over Jerusalem. In 351 AD, during the episcopacy of Cyril, a large cross-shaped light appeared in the sky. Multiple accounts describe it stretching from Golgotha to the Mount of Olives, remaining visible for days. A letter, attributed to Cyril, claimed it was brighter than the sun.

This was witnessed by large crowds across the city. It was not described as a personal revelation, but a public incident. The appearance was later commemorated in liturgical tradition. Whether interpreted as a divine sign or a warning, it was treated as a real occurrence, recorded and preserved by Church authorities.

In Constantinople (447 AD), a strange abduction occurred in plain sight during a series of earthquakes. Emperor Theodosius II and Patriarch Proclus were leading public prayers in the streets asking for God’s mercy. During one of these gatherings, a young boy was reportedly lifted into the air by an unseen force. He was lifted so high, the people on the ground lost sight of him.

He eventually floated back down to the ground and reported that he had been surrounded by glowing beings that sang hymns in a language he couldn’t understand.

Bishops at the time wrote that the entire crowd saw it. Modern terminology would call this event a mass sighting but in the fifth century, it was treated as a message and a sign of divine intervention.

As I moved forward in time, I found that these phenomena continued to appear at decisive moments that shaped recorded history and Christian tradition.

In 507 AD, on the fields near Poitiers, Clovis I, king of the Franks, was engaged in a battle against the Visigoths. His forces were weakening. According to accounts rooted in Gregory of Tours and later chroniclers, a bright light appeared in the night sky and remained suspended above the field.

It did not streak like a meteor or pass like a comet. It held position, then moved ahead, as if leading the army. Clovis followed it and by the morning, the Visigothic king, Alaric II, was dead and the tide of battle had turned. Clovis converted to Catholicism soon after. This one conversion tied the emerging country of France to the Roman Church for centuries.

Chroniclers recorded this light as the decisive factor in the victory. The Church remembered it as providence.

In 540 AD, another event was documented by Benedict of Nursia, the founder of Western monasticism. He was praying at dawn at Monte Cassino and, according to Gregory the Great in his Dialogues, Benedict saw a light break across the night sky, intensify, and form into a globe of fire. Within it, he saw the soul of Germanus, Bishop of Capua, being carried upward towards heaven.

Benedict called for his deacon, who arrived in time to see the fading light of the orb. Days later, messengers confirmed that Bishop Germanus had died at the exact hour of Benedict’s vision.

Gregory emphasized that Benedict insisted this was not an inward vision but a real orb. He treated it as an objective event. Benedict believed he had seen a soul transported. The Church preserved this story as a miracle.

Around 675 AD, a similar phenomenon occurred at the Barking Abbey in England. Nuns were keeping vigil over the graves and according to Bede, in his Ecclesiastical History, a bright light descended like a sheet, circled the ground, and then rose back into the sky.

The nuns were so shaken that they stopped praying. The event was later interpreted as a sign marking the place where their own bodies would one day rest before resurrection. It was neither an apparition nor a vision. It was treated as a geographical message, delivered through light.

These women were not seeking visions. They were keeping the traditional hours of prayer. Whatever they saw, it disrupted routine, instilled fear, and remained in the record of the English Church.

In the early ninth century, in Lyon, under Archbishop Agobard, rumors spread among the people of aerial ships from a place they called Magonia. According to popular belief, sailors descended from the clouds to steal crops during storms.

Four individuals were accused of falling from these mysterious sky ships and were nearly executed. Archbishop Agobard intervened to stop the murder. He declared the beliefs superstitious and condemned the attempted killing. Yet in arguing against the story, he wrote it down in full.

In his treatise On Hail and Thunder, Agobard unintentionally preserved one of the earliest references to flying vessels in European history. The bishop did not believe it but his account confirms that a widespread belief in aerial craft existed long before modern sightings.

In 1425, in the village of Domrémy, a thirteen-year-old girl named Joan began reporting visitations. According to the records from her later trial at Rouen, she said that the beings were often surrounded by light. Like the previous accounts, these were not described as visions. They were recorded as real encounters. One inquisitor asked directly if she saw the light with her physical eyes, and she answered yes.

She identified St. Michael, St. Catherine, St. Margaret as the beings visiting her. They directed her to take up arms and lead armies. Within two years, she was altering the course of the Hundred Years’ War.

Centuries later, when the Church revisited her case, it concluded that her voices were genuine and canonized her as a saint. Modern interpretations often reduce her to political symbol or psychological case. But the documentation, taken at face value, describes repeated contact with a luminous intelligence that issued instructions with national consequences.

In 1531, on Tepeyac Hill near Mexico City, an event occurred that would lead to one of the largest mass conversions in history. Juan Diego, an indigenous farmer, reported that a radiant woman appeared to him and requested a chapel be built on the hill they stood on. After sharing his story with a local bishop, the bishop demanded proof.

According to the earliest written account, the Nican Mopohua, Juan Diego returned with his cloak filled with roses out of season. When he opened it, an image was imprinted on the fabric that he used to carry the roses. The image shows The Virgin Mary surrounded by rays of light, wearing stars and standing on a crescent. The tilma still survives today.

Whatever you believe about this image, its impact is undisputed. Millions entered the Church in the following years. Popes have referenced the tilma as both icon and mystery. Scientific examinations of the fabric have raised more questions than answers.

These accounts point to the reality of an unseen realm that directly intervenes in human affairs. Across every century, these events follow a pattern. They appear in moments of upheaval, they intervene, and then history is changed.

To call them “contact” is to use modern language for an ancient reality. The people who saw these things did not describe visitors from another world. The Church gave them names: angels and demons. Real intelligences, acting with purpose and free will. And as far as I can tell, angels and demons are a much better explanation for these sightings than visitors from another planet. I believe they are messengers from the other side, intervening when we need them most. Since they once saw it fit to guide kings and saints, what does it mean that we still see them today?

Recommended Reading:

American Cosmic: UFOs, Religion, Technology by D.W. Pasulka

Encounters: Experiences with Nonhuman Intelligences by D.W. Pasulka

🔍 Watch the full interview with Diana for free here on Substack or in my YouTube Members area.

If you’re drawn to the hidden, the sacred, and the strange, please consider subscribing to my YouTube channel!

Subscribe: https://www.youtube.com/@tayjmcm

Primary Historical Sources Referenced

Siege of Jerusalem (70 AD) – Sky Armies

Flavius Josephus – The Jewish War, Book VI

The Cross of Light over Jerusalem (351 AD)

Letter attributed to Cyril of Jerusalem

Describes the luminous cross stretching from Golgotha to the Mount of Olives.Referenced by later Church historians such as Socrates Scholasticus and Theodoret of Cyrrhus.

Boy Abducted in Constantinople (447 AD)

Accounts preserved in:

Proclus Homilies:

Theophanis chronographia:

Caesar Baronius Volume 6:

Chronicon paschale:

Patrologia Latina:

Clovis I & the Orb of Light at Poitiers (507 AD)

Gregory of Tours – Historia Francorum (History of the Franks)

Chronicon Fredegarii (7th Century)

Liber Historiae Francorum (c. 727 AD)

Chronicon Moissiacense (8th Century)

Hagiographies of Saint Remigius and Clovis

Benedict of Nursia & the Fiery Sphere (540 AD)

Pope Gregory the Great – Dialogues, Book II

Barking Abbey Light Phenomenon (c. 675 AD)

The Venerable Bede – Ecclesiastical History of the English People, Book IV

Aerial Ships & Magonia (c. 815 AD)

Agobard of Lyon – De Grandine et Tonitruis (On Hail and Thunder)

Joan of Arc’s Visitations (1425–1431)

Trial Records of Rouen

Later reaffirmed in the Nullification Trial (1456).

9️⃣ Apparition of Our Lady of Guadalupe (1531)

The Nican Mopohua (Nahuatl account, 1649, attributed to Antonio Valeriano)

Earliest written narrative of Juan Diego, the roses, and the tilma image.